Alban Gerhardt

The Prague Spring announces that the American cellist Alisa Weilerstein will not be able to perform at this year’s festival.

Programme

- Johann Sebastian Bach: Cello Suite No. 1 in G major BWV 1007

- Johann Sebastian Bach: Cello Suite No. 2 in D minor BWV 1008

- Johann Sebastian Bach: Cello Suite No. 3 in C major BWV 1009

- Johann Sebastian Bach: Cello Suite No. 4 in E flat major BWV 1010

- Johann Sebastian Bach: Cello Suite No. 5 in C minor BWV 1011

- Johann Sebastian Bach: Cello Suite No. 6 in D major BWV 1012

Performers

- Alban Gerhardt - cello

Price

Expected end of the event 22.00

Venue

Prague Returns

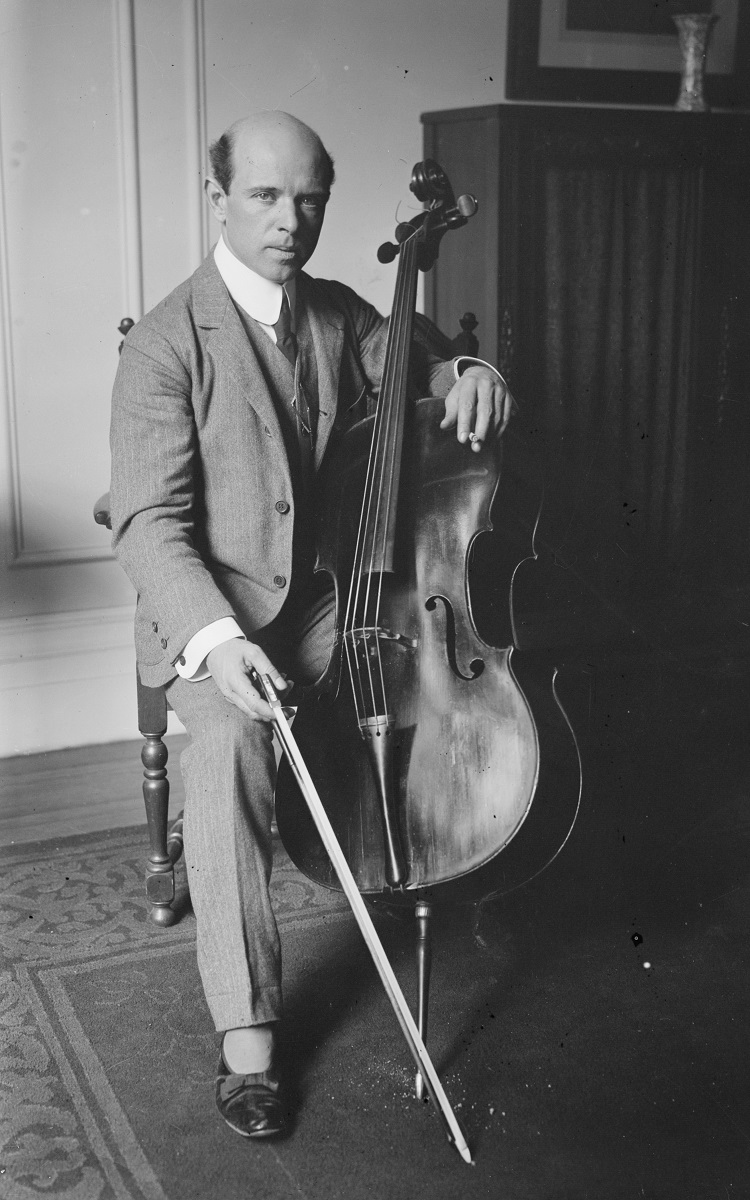

Alban Gerhardt began his extraordinarily successful and artistically rich career in 1991, when the German cellist appeared with the Berlin Philharmonic and the conductor Semyon Bychkov. Since then, Gerhardt has been one of today’s most acclaimed cellists. His repertoire ranges from the compositions of Johann Sebastian Bach to the music of the most prominent contemporary composers who have written works for him.

Gerhardt is well known to the Czech public from his 2010 Prague Spring appearance, when he played Antonín Dvořák’s Cello Concerto in B minor with the Janáček Philharmonic of Ostrava and the conductor Petr Altrichter. Recently he has been returning to Prague regularly as a guest of the Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra and its chief conductor Alexander Liebreich.

His personal ascent of Mount Everest

Bach’s Six Suites for Solo Cello are mainstays of Gerhardt’s repertoire. When he recorded them in 2019 on the British label Hyperion, the prestigious journal Gramophone wrote: “Gerhardt can sound deliciously at ease in this music, whether moving with swift grace through a Sarabande or skipping with jaunty assurance through a Menuet or Gavotte. And his sound is glorious – a silvery tenor register (…) capping an overall tone that is rich without ever being overbearing.” Gerhardt has called the recording of the complete cello suites his personal ascent of Mount Everest.

According to him: “Every cellist dreams of being able to say something meaningful by playing Bach’s Cello Suites, which are considered the ‘Bible’ of the cello repertoire, thus making his or her wisdom known to the world by recording them.” Playing them all at a single concert demands great concentration and stamina, and there are few cellists who dare to take the challenge. After all, for nearly three hours he will be alone on stage with just his cello, which happens to be a superb instrument from the workshop of the Venetian master luthier Matteo Goffriller (1710).

Respect for the music

German composer Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) wrote the suites during his time in Köthen between the years 1717 and 1723. The suite as a Baroque form contained four principal dances – the allemande, courante, sarabande and gigue; in his suites for solo cello Bach also included preludes, minuets, bourrées and gavottes. Originally, these suites were regarded more as instructive pieces; however, after public performances by Pablo Casals, one of the most important cellists of the 20th century, they became popular concert items. It was Casals, creator of the modern style of cello playing incorporating the whole body, who considered the Bach suites as the ultimate repertoire for this instrument. He also wrote a transcription of the sixth suite for the contemporary cello since Bach had a five-string instrument in mind instead of the four strings used today.

Casals’ pre-eminence is also reflected in his performance of these suites, for he began playing them together as a set and did not merely select individual dances. He defended the use of the modern instrument for the interpretation of early music: “If one wants to undertake an interesting, though always incomplete, reconstruction of the musical atmosphere of a period, I accept the use of instruments of that period. But in any ordinary performance we ought to make use of the best instruments available nowadays, for, in my opinion, respect for the music we perform must be above all other considerations. We don´t want to conjure up the past on a historical basis (which is always only relatively exact), but to produce the best version from a musical viewpoint. […] Therefore, in order to get an “authentic” reconstitution, we would have to make the flutes and the oboes play out of tune and ask all the string players to play in a mediocre way. No, to submit oneself to archaic practices in playing Bach would only do harm to his music, which rises above the past, present and future.” This is an extract taken from Conversations with Casals by J. Ma. Corredor, published in 1957 (transl. André Mangeot). At that time, of course, the period interpretation of early music was in its initial stages. Much has happened since then, and today’s performers have at their disposal a broad palette of possible ways to interpret Bach.