Closing Concert

Programme

- Sofia Gubajdulina: Märchen-Poem

- Dmitri Shostakovich: Symphony No. 9 in E flat major Op. 70

- Antonín Dvořák: Symphony No. 6 in D major Op. 60

Performers

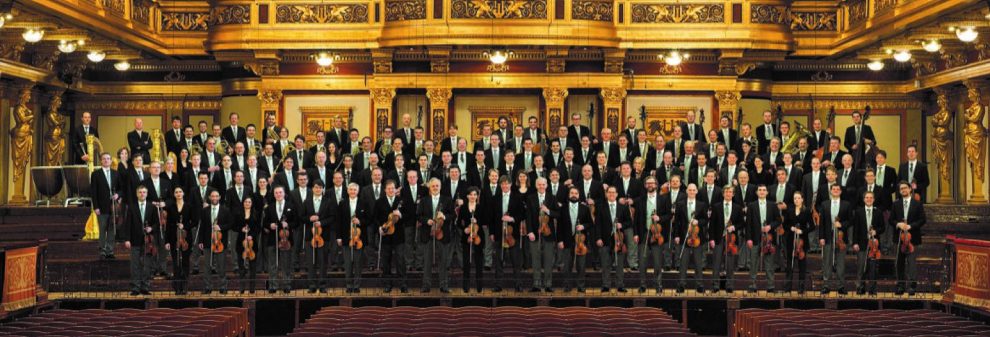

- Wiener Philharmoniker

- Andris Nelsons – conductor

Course of music history

“One could hardly find an ensemble that is more tightly bound to the history and traditions of European classical music than the Vienna Philharmonic, an orchestra that is rated one of the very best in the world”, says Roman Bělor, director of the Prague Spring Festival. For more than half a century, the orchestra has been one of the regular guests to the Prague Spring Festival—from the concerts with Herbert von Karajan and Karl Böhm in the 1960s to the unforgettable opening concert with Daniel Baremboim in 2017. In 2022 the orchestra will be commemorating the 180th anniversary of its founding, during which time it has been setting the course of music history. To this day it preserves its unique “Viennese sound”, which differs from that of other orchestras and is passed from one generation to the next. “We are overjoyed that one of the world’s best orchestras will be appearing at the festival’s closing, and especially with a conductor of such importance as Andris Nelsons”, says Bělor. “I am particularly pleased that Antonín Dvořák’s Symphony No. 6 has been selected as the final work on the programme, and on the first half of the concert we can look forward to the refreshing combination of Dmitri Shostakovich and Sofia Gubajduilna, who is truly one of the living classics”, explains the festival programming director Josef Třeštík. The Chairman of the Vienna Philharmonic, Daniel Froschauer, adds: “The work by the non-conformist Russian is based on a Czech fairy tale about erudition and fantasy. This will be followed by the Ninth Symphony by Dimitri Shostakovich, Gubaidulina’s mentor – a musical balancing act with much hidden irony and criticism of the regime. As a sign of the close ties with our neighbours, we chose Antonín Dvořák’s Sixth Symphony. With this cheerful, humorous tone poem, he set a monument to his Bohemian homeland.”

Democratically run organisation

Since its founding in 1842 by Otto Nicolai, the Vienna Philharmonic has been cooperating with prominent conductors and composers. They maintain their stable position as a unique ensemble partly on the basis of the original idea of a democratically run organisation with artistic and organisational operations in the hands of the musicians themselves, including the choice of repertoire, soloists, and conductors, and in part through their close association with the Vienna State Opera, a pillar of that association being the stipulation that only a member of the orchestra of the Vienna State Opera can become a member of the Vienna Philharmonic. Until 1933, the players elected a conductor to lead all of the concerts of their subscription season. Among them were such conductors and composers as Felix Otto Dessoff, Hans Richter, Gustav Mahler, and Wilhelm Furtwängler. Afterwards they abandoned that practice and implemented a system of guest conductors including Arturo Toscanini, Bruno Walter, Karl Böhm, Claudio Abbado, Zubin Mehta, Herbert von Karajan, and Leonard Bernstein. Today, the world’s best conductors still work with the Vienna Philharmonic, including Daniel Barenboim, Riccardo Muti, Christian Thieleman, and Andris Nelsons.

The most extraordinary orchestra in the world

Each year, the orchestra gives 40 concerts on its home stage including the famous New Year’s Concert broadcast around the world, and it gives around 50 performances on tours abroad. It has a rich discography to its credit encompassing, among other things, the complete symphonies of Beethoven, Brahms, and Mahler. For its artistic activities, it has received countless awards and the praise of music critics and of musicians. Richard Wagner described the ensemble as the most extraordinary orchestra in the world, Anton Bruckner called it “the best association of musicians in the world”, Johannes Brahms was counted among its “friends and admirers”, and Gustav Mahler said he felt himself to be “bonded by the art of music” to the orchestra. The Vienna Philharmonic performed in Prague for the very first time in 1934 in Smetana Hall at the Municipal House with Arturo Toscanini conducting. They first appeared at the Prague Spring Festival in 1963 under the baton of Herbert von Karajan with music by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Richard Strauss, and Johannes Brahms. They have also appeared at the festival with Karl Böhm (1967), Leopold Hager (2006), Christoph Eschenbach (2014), and repeatedly with Daniel Barenboim, whose performance of Smetana’s Má vlast in 2017 was one of the most important events in the modern-era history of the festival.

With the best only

Andris Nelsons (1978), one of today’s most renowned conductors and the winner of several Grammy Awards, has been the music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra since the 2014/2015 season, and since February 2018 the 21st “Kapellmeister” of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra. With both orchestras, he is realising his vision as a conductor, giving warmly received tours with them and taking the initiative in cooperation between them, the highpoint so far having been a concert held in the autumn of 2019 in Boston where an orchestra appeared that consisted of the musicians of both ensembles. Nelsons also collaborates regularly with the Berlin Philharmonic, the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra in Amsterdam, and the Vienna Philharmonic, which he conducted in 2020 for their prestigious New Year’s Concert and on the occasion of the celebrations of the 250th anniversary of Ludwig van Beethoven’s birth, when he led that orchestra in a cycle of Beethoven’s symphonies at the Philharmonie de Paris, the Gasteig in Munich, and the Elbephilharmonie in Hamburg. He is also a regular guest at the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden and at the Bayreuth Festival.

An indefinable connection

Music critics around the world praise his work with orchestras. “Whether he’s conducting the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra in Bruckner or the Vienna Philharmonic in Beethoven, Andris Nelsons is mindful of the profound, indefinable connection between a conductor and his musicians”, wrote the prestigious British journal Gramophone. And according to the Boston Classical Review, “Nelsons led the work with a firm sense of momentum while highlighting its many details”. Nelsons’s exclusive contract with Deutsche Grammophon has led to several extraordinary recording projects, including the complete symphonies of Shostakovich (with the Boston Symphony Orchestra), Bruckner (with the Gewandhaus Orchestra), and Beethoven (with the Vienna Philharmonic). Nelsons’s early career was also remarkable. A native of the Latvian city Riga, he was playing trumpet in the orchestra of the Latvian National Opera even before his conducting studies. Later, he was music director of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra (2008–2015), chief conductor of the Northwest German Philharmonic in Herford (2006–2009), and from 2003 to 2007 music director of the Latvian National Opera.

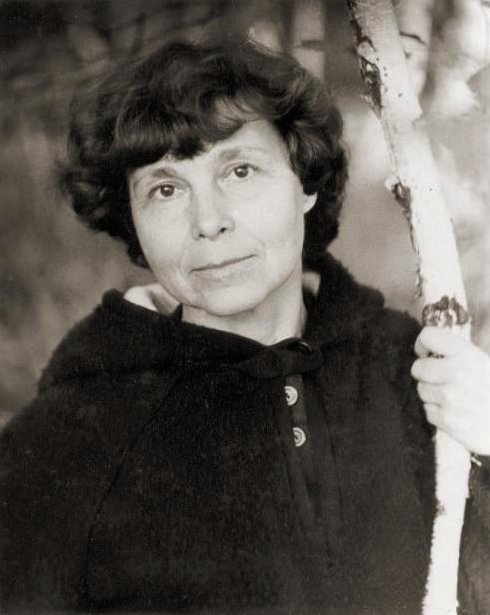

A beauty is an eternal presence

The Russian-Tatar composer Sofia Gubajdulina (*1931) has been living in Germany since 1992 in a rural area near Hamburg. After emigration, she acquired considerable international fame, which earned her commissions from important performers and prestigious institutions and festivals around the world. Her path to the limelight was neither short nor easy. Gubajdulina studied composition at the Moscow Conservatoire, but like many composers of her generation such as Alfred Schnittke or Edison Denisov who rejected the official aesthetics of Socialist Realism, she was far more influenced by the “unofficial” aspects of her studies, which consisted of independent learning from scores and recordings of New Music from western Europe, reading illegal samizdat literature, and attending gatherings of circles of likeminded artists. At the turn of the 1960s and ’70s, Gubajdulina established rather close ties to the Czech cultural milieu, and especially to the composer Marek Kopelent, for whose ensemble Musica Viva Pragensis she wrote a new composition titled Concordanza in 1971. It probably is no coincidence that in that same year she also composed Märchen-Poem (Fairy Tale Poem), an early orchestral work, the material of which was taken from the composer’s music for a radio dramatisation of the fairy tale Křída (Chalk) by the Czech author Miloš Macourek.

“At the beginning there is a piece of chalk in a cardboard box with other big pieces of chalk. It lies there dreaming about the beautiful things it will draw in its life”, the fairy tale tells us. The chalk would like to draw “the sea with a lighthouse and ships sailing in the distance against the background of chalk cliffs, the sun reflecting on the blue surface, a big airship full of banners flying around a little white cloud, white like chalk, high above the roofs of houses and above gardens with pavilions”… The chalk does not cease to believe its dreams even when it has been used up and is now very tiny. Or as the poet Josif Brodsky writes in his book Watermark: “We depart, while beauty remains. For we are heading for the future, but beauty is an eternal presence.”

Programme Notes

After the huge success (on a scale scarcely imaginable these days) of Shostakovich’s Seventh or Leningrad Symphony, which became a worldwide symbol of cooperation and united purpose in the struggle against fascism thanks to the efforts of Soviet propaganda and America’s marketing machinery, Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich (1906–1975) achieved a level of social and political recognition beyond the wildest dreams of perhaps any other artist of the 20th century. Then when the Eighth Symphony continued along the lines of the monumentality and intellectual seriousness of its predecessor, one can hardly be surprised by the expectations in 1945 surrounding the Ninth Symphony, which was supposed to have been a grandiose celebration of the heroism of the Soviet people and their victory over fascism.