Closing Concert

The rights for publishing of the recording on this website have expired on July 2, 2021.

This concert will take place with an audience in the hall.

You can already buy tickets now. For more information please click here.

Did you already purchase your tickets?

News tickets and instructions have been already sent. Should you have any questions, contact our Help desk +420 461 049 232.

Programme

- Gustav Mahler: What the Wild Flowers Tell Me, 2nd movement from Symphony No. 3, arranged by Benjamin Britten

- Benjamin Britten: Les Illuminations Op. 18 for high voice and string orchestra

- Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 6 in F major Op. 68 “Pastoral”

Performers

- Czech Philharmonic

- Mark Wigglesworth – conductor

- Petr Nekoranec – tenor

Benjamin Britten – Les Illuminations

English translation please download here.

We need to regain our confidence

“It will be very special to perform at the Prague Spring Festival in a year in which so much healing has to begin. We need to regain our confidence, a confidence that can be led by the arts. The Prague Spring Festival has always had faith in the future. We need to share that faith now more than ever”, maestro Wigglesworth says.

Internationally acclaimed British conductor Mark Wiggleshorth (1964) is sought after by opera houses and symphony orchestras all over the world. His detailed performances combine a finely considered architectural structure with great sophistication and, moreover, with a rare beauty that never fails to stir his audiences. His interpretation of Britten’s War Requiem in Cardiff in 2018 was “one of the most visceral and heart-rending… he portrayed the drama of Britten’s choral and orchestral writing as thrillingly as any I remember,” wrote Hugh Canning in The Sunday Times. The conductor is highly respected and well-liked in his native country; in 2017 he received the prestigious Laurence Olivier Award for excellence in the field of opera.

Wigglesworth has close connections with the English National Opera, where he has conducted many works, from Mozart to Leoš Janáček and Alban Berg; he also spent a relatively brief period as its Music Director. He has been collaborating since 2002 with another celebrated opera venue in London – the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden, where he was involved in a production of Janáček’s From the House of the Dead. He is regularly invited to the Metropolitan Opera in New York, and his debut there in 2005 with The Marriage of Figaro was critically acclaimed: “From the first measures of the overture I realized that this was something out of the ordinary,” wrote Raymond Beegle in a review for the notable American music magazine Fanfare.

Programme note

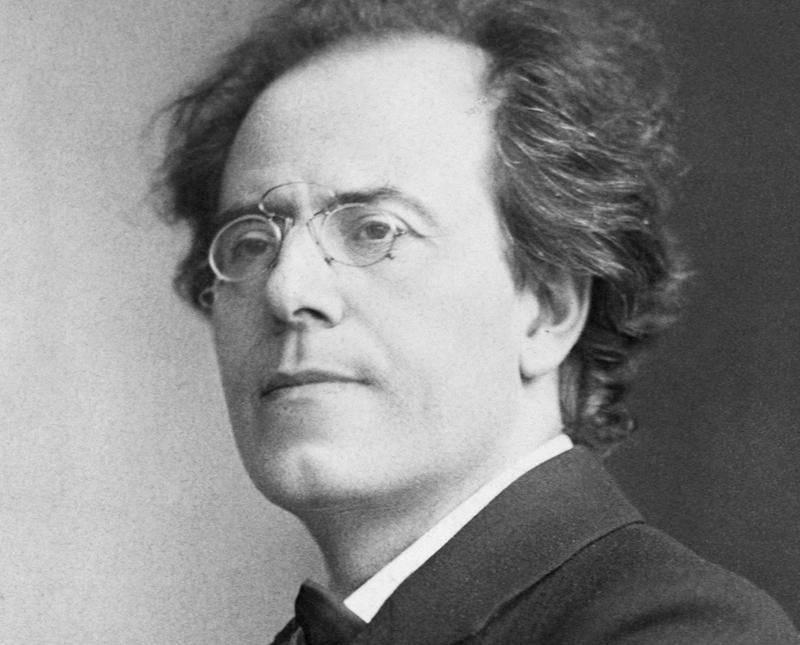

The symphonies of GUSTAV MAHLER (1860–1911) stand on the boundary line between programme and absolute music, two of the movements characterising 19th century orchestral writing. Ludwig van Beethoven, a master of musical structure, endured as a major compositional example and, under the influence of literature, philosophy and other spheres of knowledge, new subject matter found its way into music. Mahler wrote Symphony No. 3 in the years 1892–1896. Its individual parts originally had programme titles, and the symphony as a whole was to have been called The Gay Science after the book of the same name by Friedrich Nietzsche. The first movement “Pan Awakes. Summer Marches In” was a celebration of the rebirth of nature; the second was known as “What the Wild Flowers Tell Me”; the third was “What the Animals in the Forest Tell Me”; the fourth movement originally bore the designation “What Man Tells Me”, followed by “What the Angels Tell Me”; and the final Adagio was entitled “What Love Tells Me”. Mahler later abandoned his titles, however, they were not forgotten and the symphony’s programme subtext remained.

BENJAMIN BRITTEN (1913–1976 ) first encountered Mahler’s music in 1930 as a student at London’s Royal College of Music when he heard the latter’s Fourth Symphony at a concert given in Queen’s Hall: “After that concert, I made every effort to hear Mahler’s music, in England and on the continent, on the radio and on the gramophone, and in my enthusiasm, I began a great crusade among my friends on behalf of my new god – I must admit with only average success,” wrote Britten in his 1942 article for Tempo magazine “On Behalf of Gustav Mahler”. “[…] It will be realized therefore how glad I was to hear that Messrs. Boosey & Hawkes were considering bringing out several of the movements from the Symphonies of Mahler in separate editions and for slightly reduced orchestras, and how anxious I was to co-operate.” Encouraged by musician and writer Erwin Stein (1885–1958), Britten arranged the second movement of Mahler’s Symphony No. 3 for small orchestra in 1941, namely at a time when the National Socialists on the Continent were endeavouring to erase Mahler’s name from musical history. Stein, an editor for the Vienna-based music publisher Universal Edition, fled to Great Britain to escape Nazism and became an employee of Boosey & Hawkes, where he continued to promote works by composers banned by the Nazis. Britten’s arrangement of Mahler’s symphonic movement was published by this firm in 1950 under the title What the Wild Flowers Tell Me. He stayed faithful to Mahler’s original, nevertheless, the smaller instrumental group lends the work a greater, romanticising intimacy.

Benjamin Britten’s song cycle with orchestra Les Illuminations, set to texts by French poet Arthur Rimbaud, originated in wartime. Arthur Rimbaud (1854–1891) started work on a collection of prose poems in 1871 which he continued the following year when, together with his friend Paul Verlaine, another of the “poètes maudits”, he travelled on a tour of England and Belgium. The title of the collection, Les Illuminations, was a suggestion from Verlaine; it was first published in 1886. Rimbaud described his take on the world as a “philosophy of barbarism” and maintained that “the idea is to reach the unknown by the derangement of all the senses.” Likewise, “barbarism” was a term initially ascribed to Mahler’s music, and the composer also shared in Rimbaud’s vehement pursuit of the meaning of life. We will find further associations when we consider the fact that Britten’s musical setting of the poet’s opus was written for Swiss soprano Sophie Wyss (1897–1983), through whose performances he discovered Mahler’s song oeuvre.

Britten began composing his cycle in April 1939 during his voyage to the United States, where he completed the piece five months later. Rimbaud’s text declares in the introductory Fanfare: “I alone have the key to this wild parade”; the sentence occurs several times during the course of the cycle, like a compositional cipher. Villes depicts the bustle of the city and its diversity through a comparison with ancient bacchanalia and other mythological scenes; via the segment Phrase, about notional connecting lines, the composer moves to the part Antique, another classical image – here a tribute to the pagan deities Pan and Dionysus, expressed in a broad melodic line and a gentle waltz rhythm. Royauté is an ironic mockery of human pride, while the exquisite charm of the coastal landscape in Marine is rendered with an almost childlike eagerness. The poem Being Beauteous, which Rimbaud gave an English title, speaks of the beauty of dying, of the nobility of the wounds which mark the dying body, and of the transition to a new life. Parade is ablaze with colour amid a curious masquerade. The cycle ends with Départ: “Seen enough”…

The work was premiered in London’s Aeolian Hall on 30 January 1940 by soloist Sophie Wyss accompanied by the Boyd Neel String Orchestra. The songs can also be sung by a tenor; the first performance of the piece in this vocal range was given by Britten’s life partner, Peter Pears.

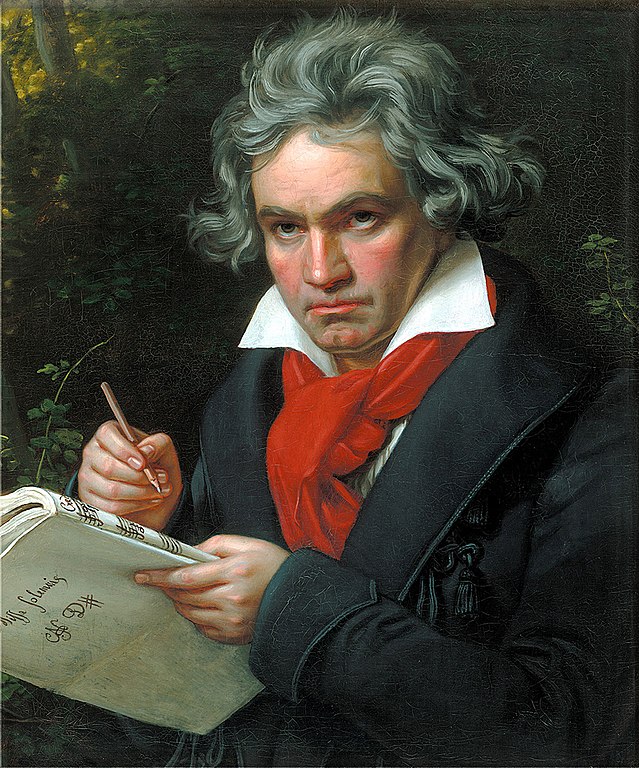

On 22 December 1808 the Theater an der Wien in Vienna hosted the premieres of two symphonies by LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770–1827), Symphony No. 5 in C minor Op. 67, which later received the nickname “Fate”, and Symphony No. 6 in F major Op. 68, with its subtitle “Sinfonia pastorale”. Both symphonies were written almost concurrently and were published with successive opus numbers. The two works have much in common yet, in many respects, they are also diametrically opposed.

Symphony No. 6 in F major “Pastoral” is a programmatic work. In Beethoven’s time such compositions were not exceptional; there were numerous pieces in existence bearing titles suggestive of natural phenomena or events. Beethoven’s innovative approach lay in the way he combined his non-musical subject matter with the cyclical symphonic form. The composer also gave his work a subtitle, “Erinnerung an das Landleben” (Recollections of Country Life). By adding the note “mehr Ausdruck der Empfindung als Malerei” (rather expressive of sensations than of painting), however, he was expressing the wish that his symphony would not be wrongly attributed as “music with a story”. All the same, one cannot ignore tangible examples of explicit tone colour: the depiction of a thunderstorm in the fourth movement or the clearly identifiable imitative bird calls. In his pastoral symphony Beethoven created a succession of genre images. From a formal perspective, by including five movements instead of the usual four, he was inclining towards the structure of a classical drama in five acts. The symphony later provided a model for Hector Berlioz and his Symphonie fantastique, and naturally – including the non-musical aspect – also for Gustav Mahler.

Beethoven’s era perceived the symphony as a drama, and Beethoven’s symphonic oeuvre reinforced this perception through structure, thematic treatment and inner cohesion. Carl Friedrich August Mosengeil (1773–1839) from Meiningen, whom history remembers chiefly as one of the inventors of stenography, was also a writer; when the Pastoral Symphony was published in 1809, he wrote a fervent article in which he consistently referred to Beethoven as a poet, while he described the individual movements as acts in a play. In his view, Beethoven’s musical images differed from what was customary for the time, “in the same way the work of a painter who idealises nature is distinguished from that of an ordinary copyist of it”. In the first movement “Beethoven, whose difficult compositions often make the most accomplished musicians fainthearted, is here so easy and comprehensible, so simple and childlike.” In the second movement the poet Beethoven takes a rest by a stream; the composer was later portrayed in this way in a famous lithograph. Of the third movement Mosengeil states that no-one had hitherto crafted a more authentic representation of nature. The fourth movement provides a contrast to the other movements with its harmonic fluctuations and, within the work as a whole, has the character of a sonata-form development founded on modulation. Here Mosengeil compared Beethoven, the musical dramatist, to Shakespeare. Finally, the storm recedes to make way for the popular image of a pastoral idyll, leaving the listener with “an unforgettable memory which awakens a kind of homesickness.” Mosengeil’s verbal accompaniment to the symphony wasn’t the only piece of writing inspired by Beethoven’s music; other commentaries did not differ greatly from his account, which would nevertheless still be acceptable to today’s audiences.

Vlasta Reittererová

English translation by Karolina Hughes

Petr Nekoranec

Established on the international concert and opera scene, Nekoranec is a prominent member of the young generation of singers. In the years 2014–2016 he worked with the Bavarian State Opera company in Munich and its affiliated Opera Studio, where he took on a number of vocal parts, including the title roles in Rossini’s opera Le comte Ory and Benjamin Britten’s Albert Herring. His interpretation of Albert Herring garnered him the Bavarian Art Prize. He also holds the Classic Prague Award 2017 in the category “Talent of the Year”. For a period of two years (2016–2018) he was the first Czech participant in the Lindemann Young Artist Development Program, a project run by the Metropolitan Opera in New York. From 2018 to 2020 he was engaged as a soloist at the Stuttgart State Opera, where he assumed such roles as Count Almaviva (The Barber of Seville), Don Ramiro (La Cenerentola) and Ernesto (Don Pasquale).

Nekoranec had a busy schedule planned for the 2020/2021 season yet, as has been the case for so many artists, his engagements were adversely affected by the pandemic and a number of his commitments were rearranged for a more auspicious time. These involved a tour with Cecilia Bartoli, a guest appearance at the Beethoven Festival in Warsaw, and concerts in Slovakia. He will nevertheless be appearing in the opening concert of the Smetana’s Litomyšl festival and in the Czech Philharmonic’s open-air concert in June; next season, 2021/2022, he returns to the Margravial Opera House in Bayreuth for the city’s Baroque Opera Festival, where he will reprise the role of Asprando in Porpora’s opera Carlo il Calvo. Forthcoming events include his debuts at Prague’s National Theatre (Almaviva in The Barber of Seville and Ferrando in Così fan tutte), at the National Theatre in Brno he will sing the role of Tamino (The Magic Flute), and in Toulouse’s Théâtre du Capitole he again takes on the part of Count Almaviva. In the spring of 2022 he will make guest appearances at the Stuttgart Opera as the Yurodivy in Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov.